The U.S. Bicycling Route System includes the 51.4 mile long Great Miami Riverway Alternate Route, which provides travelers with the opportunity to experience the rich history of Warren, Montgomery, and Greene Counties by traveling through quaint communities and along the urban riverfront of Dayton. Part of this alternate route connects the river towns and amenities of the Great Miami Riverway.

The U.S. Bicycle Route System (USBRS) is a developing national network of bicycle routes connecting urban and rural communities via signed roads and trails. Created with public input, U.S. Bicycle Routes direct bicyclists to a preferred route through a city, county, or state – creating opportunities for people everywhere to bicycle for travel, transportation, and recreation. Nearly 18,000 miles are currently established.

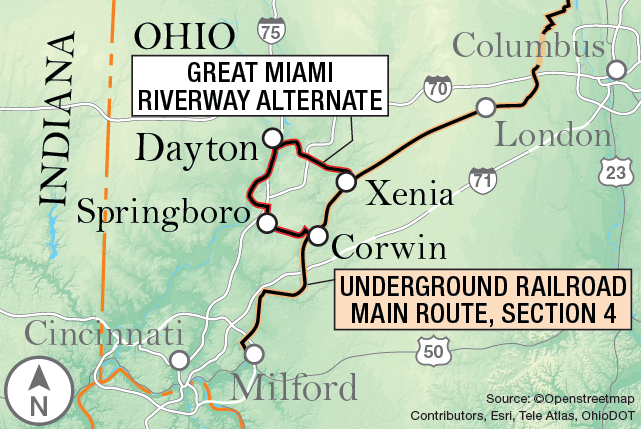

You’ll discover hidden nuggets of fascinating facts around every bend. The Alternate Route stretches from Corwin and Waynesville through Springboro on road before transitioning to off-street paved trails for the remainder of the route through Miamisburg, Dayton, and on to Xenia.

Information from https://www.metroparks.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/12/UGRR-GMR-Alt.pdf

Route Overview

The Great Miami Riverway Alternate (GMRA) provides travelers the opportunity to experience the rich history of Warren, Montgomery, and Greene Counties by traveling through quaint communities and along the urban riverfront of Dayton, an Outside Magazine Best Town. You’ll discover hidden nuggets of fascinating facts around every bend. You’ll travel from Corwin and Waynesville through Springboro on road before transitioning to off-street paved trails for the remainder of the route through Miamisburg, Dayton and on to Xenia. Miamisburg is also proud to be the Sister City to Owen Sound, Ontario; the northern terminus of the Underground Railroad Bicycle Route (UGRR).

The GMRA will lead you over rolling hills and through river valleys while traveling predominantly on dedicated paved trails. The Miami Valley is the home of the Nation’s Largest Paved Trail Network where you can experience over 340 miles of connected trails (miamivalleytrails.org). Dayton is among several bicycle friendly communities and is steeped in tradition with a solid outdoor recreation scene including paddling hot spots such as the RiverScape River Run and the Mad River which are both along the route tucked among several of Five Rivers MetroParks and other public land.

This growing scene has earned Dayton the title of “The Outdoor Adventure Capital of the Midwest!”. Check it out at outdoordayton.com, more on the Great Miami Riverway at greatmiamiriverway.com.

While long distance cyclists on the UGRR have a 51 mile alternate route to experience the rich history along the GMRA; local cyclists can experience a weekend tour by choosing to loop back to their starting point using the Little Miami Scenic Trail to create a 65 mile mini-tour with B&B and camping opportunities at several places along the route.

In addition to the UGRR and GMRA, the region is at the crossroads of several long distance cycling options including the Ohio to Erie Trail and Adventure Cycling’s Chicago to New York City (CNYC) route along with U.S. Bicycle Route 50 and 25.

The Waterways Leading to Freedom

The Great Miami River and the Miami Erie Canal transported goods supporting the farming, mining, and other industries developing in Southwest Ohio in the 19th century but it also carried more than supplies and traveling passengers on their way to see family and friends; it is believed vessels traveling these routes also carried slaves traveling to freedom via the Underground Railroad.

Both the Great Miami River and remnant of the Miami Erie Canal lead into Dayton, Ohio; a town known for many inventions including the first plane, the first cash register, and the soda can pop tab, as well as some local history tied to the Underground Railroad. One such runaway slave that may have used the Underground Railroad to reach Dayton is Paul Laurence Dunbar’s father, who also served in the famous Massachusetts’s 55th Infantry during the Civil War. The emancipation of slaves after the Civil War paved the way for Dunbar to become the first nationally-recognized African American Poet. During his short lifetime, Dunbar would write poems for esteemed magazines like The New York Times and Harper’s Weekly, as well as publish twelve books of poetry, four novels, four books of short stories, and lyrics to popular songs. The house he bought for his mother still stands and is part of the Dayton Aviation Heritage National Historical Park.

The Dayton Aviation Heritage National Historical Park also is home to the Wright Cycle Company Building, Hoover Block, Huffman Prairie Flying Field, the 1905 Wright Flyer III, and Hawthorn Hill. The Wright Cycle Company Building is the only building remaining of the Wright Brothers prior bicycle shop business before they invented the airplane. Hoover Block showcases the Wright & Wright, Job Printers location that published the Dayton Tattler, which was written in Dunbar’s early days as a writer specifically for the African American population in Dayton.

The first plane to fly, the 1905 Wright Flyer III, is located at Carillon Historical Park. It is the only plane to be recognized as a National Historical Landmark. Carillon Historical Park gets its name from the Carillon tower in the middle of the park, which has a set of bells hanging in the top of the tower and played much like a piano roll. Carillon Park is also home to Dayton History and preserves over three million artifacts and thirty historic landmarks.

One such of these landmarks is the Old Courthouse in downtown Dayton. Seven US presidents, including Abraham Lincoln, campaigned here during their bids for presidency. Another place of interest is the oldest building still standing in downtown Dayton (120 N. Clair St.). This building survived the Great 1913 Flood and still stands where it was originally built. There is a placard on the side of the building to indicate where the water crested during the Great Flood. Before the flood though, Samuel Brady, the homeowner during the Civil War, used his home to assist slaves escaping slavery from the South via the Underground Railroad. You can see the stark difference in architecture between homes built in the 1800s to the stylized condos next to the building now.

Another abolitionist that lived in the area was John Harries, an Englishman Brewery owner in downtown Dayton, was also an abolitionist and helped many escaped slaves using the Underground Railroad. Although his building does not exist anymore, his grave can be found at the Woodland Cemetery. Additionally, Marcus Junius Parrott is buried in the Woodland Cemetery. Parrott served in the Ohio State House of Representatives as an abolitionist and he was instrumental in making sure Kansas achieved statehood as a slave-free state just as the Civil War was beginning in 1861.

Between an Ocean and a Glacier: The Geology of the Miami Valley

As you connect to the Great Miami River Trail via the Great-Little Trail, you’ll see that the Miami Valley has many flat landscapes, but it also has rolling hills and steep valleys. The landscape that you will climb and descend was created by two different geologic time periods in Ohio’s history.

The bedrock for most of the land between Dayton and Cincinnati was formed during the Ordovician period, 505-408 million years ago, one of the warmest time periods in Earth’s history. During this time, the Miami Valley was more like a tropical sea you’d find somewhere in the Caribbean. Large hurricanes regularly swept the region, causing the sediment stirred up from the storm to settle to the bottom and capped by a layer of mud. This happened numerous times as the continent slowly drifted northward to its current location, creating over nine hundred feet of coarse, fossiliferous limestone and shale. The largest exposed Ordovician rock layer in the world is located in the Miami Valley. After the Ordovician, a big section of what is now the Midwest was uplifted, creating what is called the Cincinnati Arch. This uplifted land was subject to the forces of erosion, and over time the raised area was washed away. This resulted in much older rock being found at the surface, and a complete absence of the younger rock layers.

As the Earth entered the Ice Age about two and a half million years ago, great continental glaciers formed and spread over the region. There have been at least four continental glaciers that have covered the Miami Valley and retreated back to Canada. As the glaciers retreated they left behind piles of gravel and sand creating the hills you are biking through today. Their torrents of melting water also created gorges and filled in ancient river valleys with sand and gravel.

The Great Miami River, named after the Miami Native American Tribe that used to live in the area, winds southward to connect to the Ohio River and is a major asset for outdoor recreation enthusiasts, both in the water and on the trail you are biking on. After an incredibly harsh, cold winter in 1913 a major storm hit the Miami Valley and caused the Great Flood of 1913. As you stand at the Inventors Walk in Riverscape MetroPark in downtown Dayton, you can look across Monument Ave. to a building where a blue wave is painted, symbolic of where the water levels reached in Dayton during the flood. In the aftermath of the flood, the Miami Conservancy District was created and five earthen dams and a levee system were built around the region to prevent another catastrophic flood.