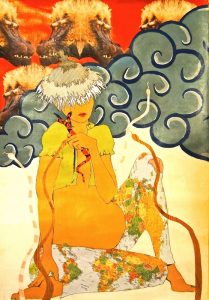

Caitlin Cartwright is a social change artist whose vibrant narrative works combine painting, drawing, and collage to explore the stories that connect people of all cultures and ages. Although her intimate works deal with themes of loss and isolation, each piece also contains elements of community, comfort, and hope

Caitlin Cartwright is a social change artist whose vibrant narrative works combine painting, drawing, and collage to explore the stories that connect people of all cultures and ages. Although her intimate works deal with themes of loss and isolation, each piece also contains elements of community, comfort, and hope

DAU—I’ve read your bio and some other online interviews. You’ve lived all over.

CC—I have moved around a bit. I am from Dayton. I grew up here.

DAU—and you moved, when?

CC—When I was 16, I moved to Cincinnati to attend the School for the Creative and Performing Arts.

DAU—That’s a great school.

CC—Yeah, it is. I had a great time there. From there I went to The Maryland College of Art.

DAU—OK, I understand moving for school and college, but how did you get from Baltimore to Madagascar?

CC—Honestly, I just started sending email to places asking if I could come. This orphanage/community center/arts organization in Madagascar answered that I could come, but I couldn’t stay there. Would I be interested in teaching at the school down the road, where this person knew they needed someone? After some email exchanges, I committed. I went to Madagascar, I taught English at the school, and as my second job, I did art projects with the orphans and street kids at the center. I painted a mural there, and just recently, I found out is still there. It’s cool to think about it.

DAU—What was it like to live in Madagascar?

CC—It was a challenge. Intimidating. Not a lot of people speak English there. The primary language is Malagasy, which I didn’t speak at all. And Madagascar was colonized by the French, so there is French spoken there, which I did not speak well.

DAU—You were so brave.

CC—I was young; it was a youth thing.

DAU—So how long did it take you to get proficient in Malagasy?

CC—It took about 7 months before I felt like I was able to hold a conversation.

DAU—And did you keep in touch with people there?

CC– There is one woman, she was my lifeline because she spoke English. We have kept in touch.

DAU—So, how long were you in Madagascar? And do you still speak Malagasy?

CC—I was there a year, and no, the vocabulary disappears after a while. I was listening to some music recently, and I could get some of the words.

DAU— And what came after Madagascar?

CC—I joined the Peace Corps and worked in Namibia. It’s beautiful there. I lived mostly outside. 90% of my time was spent outside. I had a hut, but it was mud with a metal roof, and full of gaps—it was like being outside. It was like camping. And the sky there was huge…there’s no light pollution, you know, so at night the sky is so full of stars and they’re so bright. It made me feel—-I don’t know—-it was spiritual. It was a spiritual experience.

DAU—It sounds amazing. What kind of work did you do there?

CC—I helped start a girls after-school club. We collected materials to recycle and make into baskets to sell.

DAU—And when you came back to the U.S.?

CC—Well, I wanted to do something with the community building I had been doing overseas. I thought I would get an advanced degree and grow my skill set. For some reason, I saw the community building and the art as separate, I had been sort of compartmentalizing—at least in my mind. In practice, they overlapped a lot.

DAU—So, you did both?

CC—I am doing both.

DAU—As part of that degree you went to India?

CC—I did. India was a smack in the face.

DAU—In what way? You’d traveled quite a bit.

CC—It still was a shock. You go to places, and you take your world view with you, you know. I come from such a place of privilege; and there I just realized it. I was confronted by it daily.

DAU—Tell me about that.

DAU—Tell me about that.

CC—I worked on a project that documented artists work. I would go to the artists’ houses and meet with them. There was one man who did the most beautiful metal work. I went to his house, and it was a room, more like a closet, and he and his wife and three daughters lived and worked there. His daughters weren’t going to school, because their work was good, and it sold, and it brought in money. So, no school.

DAU–I read about your project there, you’re writing was just beautiful. You talked about the caste system and the “voiceless people defined by their positions.” Another thing you said I liked was that “while artists are responsible for the beauty we see everywhere in India, they are relegated to the ugliest and most marginalized parts of society.” One of the things that really struck me about this was that by documenting their work, both you and they felt that you were “validating their existence.” That spoke to me on a larger scale, about artists in general.

CC—I know what you mean. In graduate school, in a critique, if someone “got” your work, it was a toss up whether you felt understood or exposed.

DAU—It’s probably a different feeling for artists than writers, but I hope my work will stand on its own, but I also feel like I need to explain it.

DAU—It’s probably a different feeling for artists than writers, but I hope my work will stand on its own, but I also feel like I need to explain it.

CC—Oh, I know what you mean. I always struggle with what to put on the show card. How much is too much? And yet, I love to hear the back story on works I am looking at. It adds a dimension.

DAU—And how about when someone tells you how a work makes them feel, is that a good thing or a bad thing?

CC—so far, it’s mostly good. I want people to feel things. I want my work to be evocative, visceral.

DAU—And what are you working on now?

CC—Well, I am working on a project I submitted to the Montgomery County Artist’s Opportunity grant. I was awarded funding to create a body of work responding to how our community came together after last year’s tornados and the Oregon District shooting. I want to depict that sense of community, to convey that strength and hope.

DAU—How large a body of work?

CC—Five paintings.

DAU—And do you have a deadline? Are you going to show them?

CC—I am, but I don’t know when now. It’s all up in the air. I finished the collaborative piece of the project before we were confronted by Covid-19. I worked with community members at We Care Arts on creating art about the events of last year, just letting them express themselves, and how they felt. It was a powerful experience, I really bonded with the groups as we worked. Some of the pieces are astonishing, and I plan to include their imagery in my work, with their permission, of course.

DAU—Talk to me about We Care Arts. You are director of programming there?

CC—I am, and I love it. It is the perfect place for me. I’ve always felt torn between community building and art making. We Care Arts is the intersection of the two. I don’t have to compartmentalize, I can promote art and healing, and community all at once.

DAU—And how are you coping with the Covid-19 shut down.

CC– I miss my people so much since we’ve been sheltering at home. We actually shut down on March 13, before the order came from the governor’s office. So many of our clients are in that vulnerable population. Many of them were self-isolating even before we decided to close. A big part of what I am doing every day is keeping in contact with my clients. Many of us were already feeling isolated, art is how we make connections.

We, the staff, are all doing everything we can to make sure our clients have what they need. We’re posting videos online and sending out cards. We are all checking on each other.

DAU—I liked that Amy Acton encouraged us to think about our mental health.

CC—I love her! I am so proud of us, of Ohio. I think we’re doing an amazing job of pulling together. I love that she talked about mental health. At We Care Arts, we know the impact the arts have on mental health. It’s why I think it’s so important that there are artists offering free online art classes and videoconferencing, it’s a way we can look out for each other.

DAU—Is We Care Arts offering online classes?

CC—On our web page we’re posting client pictures into our Arts at Home gallery. On our Facebook page, we’re posting video of art projects and things to keep our clients engaged. You can get to those things through the We Care Arts website or on Facebook, tagged with #WCAathome

DAU—I want to go back to something you said before. Talking about when We Care Arts shut down, you said, “Many of us were already feeling isolated,” did you mean because of Covid-19 or before Covid-19.

CC—Oh, before. At We Care Arts, we cope with all kinds of challenges: developmental disabilities, cognitive impairments, addiction, depression and a whole spectrum of issues. Alone is our journey.

We all feel like no one understands us, no one can see how we feel. Some feel that more than others. But when we share through art, we connect through art. We feel less alone because we can look at the art and see there are people who feel like we do, who know what alone is. The Covid-19 shelter at home isolation is a public enactment of how many of our clients feel all the time: alone, anxious, and uncertain about the future. It’s why we keep reaching out to each other. We need the reassurance that we will break out of this aloneness.

DAU—And when we break out? What are first things you are going to do?

CC—What won’t I do? I’m craving some Thai food, I’d like to sit down at Thai 9. I’d like to go to the Sky Bistro. I’m excited to go to the DAI summer Jazz series. I really hope that gets to happen! I went last year. My partner Duante Beddingfield sang there, and I got to go. It was such a beautiful experience. The space is so beautiful.

DAU—Caitlin Cartwright, thank you so much for talking to me. I hope we get to eat together in person soon. I look forward to going with you to the Summer Jazz Series, and to seeing your paintings on display.