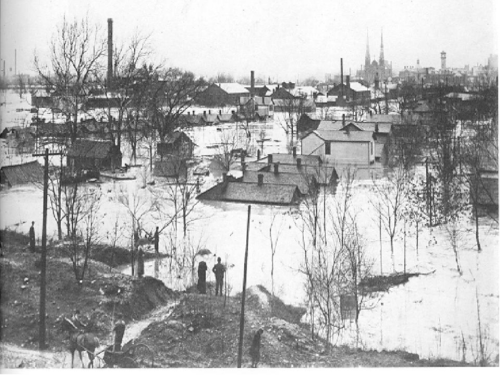

During March 1913, the citizens of the Miami Valley experienced a natural disaster unparalleled in the region’s history. Within a three-day period, nine to 11 inches of rain fell throughout the Great Miami River Watershed. The ground was already saturated from the melting of snow and ice of a hard winter. The ground could absorb little of the rain. The water ran off into streams and rivers, causing the Great Miami River and other rivers to overflow. Every city along the river was overrun with floodwater. Altogether, nearly four trillion gallons of water, an amount equivalent to about thirty days of discharge of water over Niagara Falls, flowed through the Miami Valley during the ensuing flood.

During March 1913, the citizens of the Miami Valley experienced a natural disaster unparalleled in the region’s history. Within a three-day period, nine to 11 inches of rain fell throughout the Great Miami River Watershed. The ground was already saturated from the melting of snow and ice of a hard winter. The ground could absorb little of the rain. The water ran off into streams and rivers, causing the Great Miami River and other rivers to overflow. Every city along the river was overrun with floodwater. Altogether, nearly four trillion gallons of water, an amount equivalent to about thirty days of discharge of water over Niagara Falls, flowed through the Miami Valley during the ensuing flood.

Many residents climbed to the second floor and into attics of their homes to escape death from the floodwaters that raced and swirled uncontrollably in the freezing temperatures of March. In the pitch black of night, cries for help and the eerie groaning of houses being ripped off of their foundations filled the sky as the waters continued to rise. With no functional telegraph lines, the flood survivors were completely cut off from the outside world.

Rushing torrentially, the waters swept away bridges, dwellings, and commercial buildings — and anyone who was in them. It precipitated fires at broken gas mains, which spread when fed by spilled gasoline. In Dayton, a fire erupted at a drug store, consuming nearly two blocks of business buildings (now named the “Fireblocks”). At Hamilton, within two hours the flood swept away three of the four bridges, and destroyed the fourth a few hours later.

During those long hours waiting for the waters to recede, residents made a promise to one another: Never Again.

In the Miami Valley, more than 360 people lost their lives. Property damage exceeded $100 million (that’s more than $3.2 billion in today’s economy). Despite the tragedy, the citizens of the Miami Valley, who had lost virtually everything, rallied to raise money for a plan to stop flooding once and for all. Some 23,000 citizens contributed their own money – adding up to more than 2 million dollars – to begin a comprehensive flood protection program on a valley-wide basis.

Today, reminders of how our communities overcame live on. Read below to discover eight ideas for exploring (and tasting?) Great Flood history along the Great Miami Riverway.

1. Visit Miami Conservancy District Historic Headquarters

1. Visit Miami Conservancy District Historic Headquarters

The three-story building, including basement, is built of Indiana (Bedford) limestone. Colonel Edward Deeds announced in July of 1915 that he would gift a headquarters building to the Miami Conservancy District. The building was designed and constructed in about six months, with staff moving in at the beginning of 1916. The lobby features original light fixtures, staircase and moldings. The first-floor ceilings are coffered and feature larger replicas of the original lighting fixtures.

In his letter to the Board of Directors, Edward Deeds wrote that “engineers from all quarters will be coming to the Miami Valley to study our work. We owe it to the people of the flood stricken valleys of the world to make this data complete and permanently available”.

While you are free to explore the exterior of the building (we recommend enjoying lunch in our pocket park), we recommend scheduling private tours of the interior. This is for the safety and comfort of our staff, who still use the building to this day. Please contact Sarah Hippensteel Hall via our contact form to request a tour!

More about our Headquarter Building

About the art exhibit displayed inside Headquarters

2. Admire ‘Fractal Rain’ at the Dayton Metro Library Main Campus

The impressive sculpture by Terry Welker is named“Fractal Rain”. It is is fashioned of 3,500 six-inch prisms on nearly five miles of stainless-steel wire. The dramatic piece, which hangs from the third floor under a skylight and cascades down to the floors below, changes as it catches the light at different times of day. One in every six of the prisms has been optically dyed in studio in Monet colors — lavender, green, blue, yellow, and pink.

The piece, according to Welker, references the Great Dayton Flood of 1913 and our city’s love/hate relationship with rain.

The 1,000-pound piece was selected by the internationally known Collaboration of Design and Art as one of the “top 100 most successful design projects that integrate commissioned art into an interior, architectural or public space” (From Dayton Daily News)

3. Explore the Great 1913 Flood Exhibit at Carillon Historical Park

3. Explore the Great 1913 Flood Exhibit at Carillon Historical Park

The Great 1913 Flood Exhibit features stories of disaster, perseverance, and heroism. By bringing together numerous flood-related artifacts, the exhibit tells the story of a grief-stricken city banding together to rise above adversity.

4. Taste a Piece of History at the Hamburger Wagon

4. Taste a Piece of History at the Hamburger Wagon

The famous little Hamburger Wagon in Miamisburg has some unique flood history. After the flood waters receded and disaster relief was in dire need, Miamisburg resident Sherman “Cocky” Porter used a family recipe to serve up delicious hamburgers to flood refugees for many days. When life finally returned to normal, Miamisburg residents loved the little “Porter Burgers” so much that Porter agreed to start selling them on Saturdays. The business grew from there, and ever since it has been a community staple, ranked one of the top 100 hamburgers in the United States by Hamburger America.

5. Search for Flood Depth Markers

5. Search for Flood Depth Markers

In many riverfront cities along the Great Miami River evidence of the 1913 flood depth can be found at various flood depth markers. While you are enjoying local restaurants or retail stores in one of the historic downtowns, keep your eyes peeled for these markers and statues.

Many communities along the Great Miami River such as Troy, Dayton, West Carrollton, Miamisburg, Middletown, and Hamilton have done an excellent job maintaining flood markers to showcase the height of the flood. Markers can be found as stand-alone statues, on buildings or bridges as stone or metal plaques, or can be found wrapped on light poles and fixtures. See how many you can find!

Statue in Hamilton near the Great Miami Rowing Center

High water mark at Riverscape MetroPark in Dayton

High water mark on the Market Square Building in Miamisburg

6. Follow the remnants of the Miami-Erie Canal Along the Great Miami River

The Miami and Erie Canal was 274 miles long, connecting Cincinnati to Toledo – the Ohio River to Lake Erie. Construction began in 1825 at a cost of $8 million. In today’s money? That’s $177 million. At its peak, the canal had 103 locks and featured feeder canals, man-made reservoirs, and guard stations.

As railroad systems were introduced and found to be a more reliable and cheaper mode of transporting goods, the Ohio canals saw less and less use. Various attempts at canal revival were made between 1904 and 1910, however, the Great Flood of 1913 caused the reservoirs to spill over into the canals, destroying aqueducts, washing out banks, and devastating most of the locks.

Luckily, history lives on. Throughout the Great Miami Riverway, you can find pieces of the original canal and many other places that celebrate its history. Here is a guide to view pieces of the canal today along the river. In Piqua, you can even ride the canal in a canal boat called General Harrison.

7. Take a walk through the beautiful Woodland Cemetery and Arboretum

Many flood heroes are buried like John Henry Patterson, who shut down his cash register factory to build rescue boats and provide housing and shelter to flood victims, or James M. Cox, whose leadership helped secure state aid for flood victims and establish the Miami Conservancy District. The land of the cemetery itself was a refuge for many escaping the flood waters in Dayton due to its higher elevation.

8. Visit the 5 dry dams that continue to protect the region from flooding to this day.

Within weeks of the Great Flood of 1913, community leaders hired engineer Arthur Morgan to develop a regional flood protection system, which was awarded the 1922 Engineering Record’s distinguished “Project of the Year,” placing it in a category with other international engineering design feats like the Brooklyn Bridge (1883), Eiffel Tower (1889), Empire State Building (1931), Golden Gate Bridge (1937), Gateway Arch (1965) and the Channel Tunnel (1994).

The flood protection system is designed to manage a storm the size of the Great Flood of 1913 plus an additional 40 percent. The drainage patterns of the entire Great Miami River Watershed are incorporated into its design. The 5 dry dams and 55 miles of levees operate without human intervention and have no moving parts, except floodgates on storm sewers along the levees. They are called dry because the dams are used only to store floodwaters after heavy rainfall. The remainder of the time, the storage land upstream of each dam – 35,650 acres – is used predominantly for parkland and farmland. The Miami Conservancy District partners with many park districts to enable outdoor recreation opportunities on these flood protection lands. Learn more about the system and visiting the dams with the links below:

The flood protection system is designed to manage a storm the size of the Great Flood of 1913 plus an additional 40 percent. The drainage patterns of the entire Great Miami River Watershed are incorporated into its design. The 5 dry dams and 55 miles of levees operate without human intervention and have no moving parts, except floodgates on storm sewers along the levees. They are called dry because the dams are used only to store floodwaters after heavy rainfall. The remainder of the time, the storage land upstream of each dam – 35,650 acres – is used predominantly for parkland and farmland. The Miami Conservancy District partners with many park districts to enable outdoor recreation opportunities on these flood protection lands. Learn more about the system and visiting the dams with the links below:

Dry Dams

Germantown

Taylorsville

Englewood

Huffman

Lockington