Beginner friendly, great excercise, safe and inclusive space, free to the community

The Fab Four – The Ultimate Beatles Tribute Return to Rose

If you want to experience the best Beatles tribute ever, you won’t want to miss The Fab Four – The Ultimate Beatles Tribute when they return to Rose Music Center at The Heights on Friday, June 27. The 2025 tour brings their all-new show to the stage, celebrating The Beatles’ first visit to the USA, with performances from the Ed Sullivan show and the Meet The Beatles album played in its entirety with a few greatest hits from every era. Hear your favorites including “I Want To Hold Your Hand”, ”I Saw Her Standing There”, ”All My Loving”, and so many more!

The Emmy Award-Winning Fab Four is elevated far above every other Beatles Tribute due to their precise attention to detail. With uncanny, note-for-note live renditions of Beatles’ classics such as “Can’t Buy Me Love,” “Yesterday,” “A Day In The Life,” “Twist And Shout,” “Here Comes The Sun,” and “Hey Jude”, the Fab Four will make you think you are watching the real thing.

Their incredible stage performances include three costume changes representing every era of the Beatles ever-changing career, and this loving tribute to the Beatles has amazed audiences in countries around the world, including Japan, Australia, France, Hong Kong, The United Kingdom, Germany, Mexico and Brazil.

Tickets will go on sale to the public beginning at 10AM on Friday, January 31 at Ticketmaster.com and the Rose Music Center Box Office.

Reserved Seating: $54.50* – $34.50*

The Rose Music Center box office will be open on Friday, January 31 from 10am – 3pm for The Fab Four on sale.

While supplies last. Ticket prices include parking and are subject to price increase based on demand and applicable Ticketmaster fees. All events are rain or shine.

Kawanzaa Starts Tonight

The name Kwanzaa is derived from the phrase “matunda ya kwanza” which means “first fruits” in Swahili. Each family celebrates Kwanzaa in its own way, but celebrations often include songs and dances, African drums, storytelling, poetry reading, and a large traditional meal.

The name Kwanzaa is derived from the phrase “matunda ya kwanza” which means “first fruits” in Swahili. Each family celebrates Kwanzaa in its own way, but celebrations often include songs and dances, African drums, storytelling, poetry reading, and a large traditional meal.

The candle-lighting ceremony each evening provides the opportunity to gather and discuss the meaning of Kwanzaa. The first night, the black candle in the center is lit (and the principle of umoja/unity is discussed). One candle is lit each evening and the appropriate principle is discussed.

Seven Principles

The seven principles, or Nguzo Saba are a set of ideals created by Dr. Maulana Karenga. Each day of Kwanzaa emphasizes a different principle.

Unity:Umoja (oo–MO–jah)

To strive for and maintain unity in the family, community, nation, and race.

Self-determination: Kujichagulia (koo–gee–cha–goo–LEE–yah)

To define ourselves, name ourselves, create for ourselves, and speak for ourselves.

Collective Work and Responsibility: Ujima (oo–GEE–mah)

To build and maintain our community together and make our brother’s and sister’s problems our problems and to solve them together.

Cooperative Economics: Ujamaa (oo–JAH–mah)

To build and maintain our own stores, shops, and other businesses and to profit from them together.

Purpose: Nia (nee–YAH)

To make our collective vocation the building and developing of our community in order to restore our people to their traditional greatness.

Creativity: Kuumba (koo–OOM–bah)

To do always as much as we can, in the way we can, in order to leave our community more beautiful and beneficial than we inherited it.

Faith: Imani (ee–MAH–nee)

To believe with all our heart in our people, our parents, our teachers, our leaders, and the righteousness and victory of our struggle.

Seven Symbols

The seven principles, or Nguzo Saba are a set of ideals created by Dr. Maulana Karenga. Each day of Kwanzaa emphasizes a different principle.

Mazao, the crops (fruits, nuts, and vegetables)

Symbolizes work and the basis of the holiday. It represents the historical foundation for Kwanzaa, the gathering of the people that is patterned after African harvest festivals in which joy, sharing, unity, and thanksgiving are the fruits of collective planning and work. Since the family is the basic social and economic center of every civilization, the celebration bonded family members, reaffirming their commitment and responsibility to each other. In Africa the family may have included several generations of two or more nuclear families, as well as distant relatives. Ancient Africans didn’t care how large the family was, but there was only one leader – the oldest male of the strongest group. For this reason, an entire village may have been composed of one family. The family was a limb of a tribe that shared common customs, cultural traditions, and political unity and were supposedly descended from common ancestors. The tribe lived by traditions that provided continuity and identity. Tribal laws often determined the value system, laws, and customs encompassing birth, adolescence, marriage, parenthood, maturity, and death. Through personal sacrifice and hard work, the farmers sowed seeds that brought forth new plant life to feed the people and other animals of the earth. To demonstrate their mazao, celebrants of Kwanzaa place nuts, fruit, and vegetables, representing work, on the mkeka.

Mkeka: Place Mat

The mkeka, made from straw or cloth, comes directly from Africa and expresses history, culture, and tradition. It symbolizes the historical and traditional foundation for us to stand on and build our lives because today stands on our yesterdays, just as the other symbols stand on the mkeka. In 1965, James Baldwin wrote: “For history is not merely something to be read. And it does not refer merely, or even principally, to the past. On the contrary, the great force of history comes from the facts that we carry it within us, are consciously controlled by it in many ways, and history is literally present in all that we do. It could scarcely be otherwise, since it is to history that we owe our frames of reference, our identities, and our aspirations.” During Kwanzaa, we study, recall, and reflect on our history and the role we are to play as a legacy to the future. Ancient societies made mats from straw, the dried seams of grains, sowed and reaped collectively. The weavers took the stalks and created household baskets and mats. Today, we buy mkeka that are made from Kente cloth, African mud cloth, and other textiles from various areas of the African continent. The mishumaa saba, the vibunzi, the mazao, the zawadi, the kikombe cha umoja, and the kinara are placed directly on the mkeka.

Vibunzi: Ear of Corn

The stalk of corn represents fertility and symbolizes that through the reproduction of children, the future hopes of the family are brought to life. One ear is called vibunzi, and two or more ears are called mihindi. Each ear symbolizes a child in the family, and thus one ear is placed on the mkeka for each child in the family. If there are no children in the home, two ears are still set on the mkeka because each person is responsible for the children of the community. During Kwanzaa, we take the love and nurturance that was heaped on us as children and selflessly return it to all children, especially the helpless, homeless, loveless ones in our community. Thus, the Nigerian proverb “It takes a whole village to raise a child” is realized in this symbol (vibunzi), since raising a child in Africa was a community affair, involving the tribal village, as well as the family. Good habits of respect for self and others, discipline, positive thinking, expectations, compassion, empathy, charity, and self-direction are learned in childhood from parents, from peers, and from experiences. Children are essential to Kwanzaa, for they are the future, the seed bearers that will carry cultural values and practices into the next generation. For this reason, children were cared for communally and individually within a tribal village. The biological family was ultimately responsible for raising its own children, but every person in the village was responsible for the safety and welfare of all the children.

Excerpted from the book: The Complete Kwanzaa Celebrating Our Cultural Harvest. Copyright 1995 by Dorothy Winbush Riley.

Downtown Dayton River Kayaking Trips

Kayak down the Mad River and the Great Miami River through the two whitewater features of the RiverScape River Runs. This trip is led by Five Rivers MetroParks staff and equipment is provided. There is a chance you could tip over while kayaking and we will be getting wet so please dress appropriately including wearing water shoes, or old sneakers. This trip will include paddling through Class II-III whitewater rapids and will require you to actively paddle much of the time.

For a description of what this means go to:

https://www.americanwhitewater.org/content/Wiki/safety:start?#vi._international_scale_of_river_difficulty )

At the end of the trip we will ride in a 15-passenger van back to the starting point where your vehicles are parked. Weather Dependent.

Dayton Rotary Foundation Opens Applications for $50,000 Grant

The Rotary Club of Dayton Foundation has just announced a grant opportunity for a nonprofit that focuses on Mental Health of up to $50,000. “Our foundation traditionally gives $3000 grants quarterly. Five years ago we gave a $50,000 signature grant to Gem City Market, and we want to again give a grant that will truly make a difference in our community,” said Foundation Board President Lisa Grigsby.

The Rotary Club of Dayton Foundation has just announced a grant opportunity for a nonprofit that focuses on Mental Health of up to $50,000. “Our foundation traditionally gives $3000 grants quarterly. Five years ago we gave a $50,000 signature grant to Gem City Market, and we want to again give a grant that will truly make a difference in our community,” said Foundation Board President Lisa Grigsby.

This Grant may used be for a single program/initiative, collaborative (multi-partner) project, operational support of an organizational project. Rotarians worldwide are currently focused on the issues of mental health.

Examples of proposed plans may include individuals/families impacted by trauma, substance use disorder, preventative care, mental health in special populations (i.e. adolescents, refugees, survivors of domestic violence, Veterans, senior adults), social determinants impacting mental health issues, suicide awareness/prevention

Proposing organizations must be IRS-qualified 501(c)3 entities located in and serving the Dayton metro region

Grant funding may used be for a single program/initiative, collaborative (multi-partner) project, operational support of an organizational project.

Signature Grant Timeline

Grant application deadline: June 13- Application available online

Send completed application to Laura Erbaugh – [email protected]

- Semi-finalists selected: July 24 (Rotary Foundation meeting)

Semi-finalists announced: July 25-28

Semi-finalist presentations at Rotary Meetings: August 12 & August 19Finalist selected by: August 28

Finalist formal announcement: September 10

Rotary is an international membership organization made up of diverse groups of people who share a passion for and commitment to enhancing communities and improving lives across the world. Rotary clubs exist in almost every country. Being a member is an opportunity to take action and make a difference.

About Dayton Rotary:

The Rotary Club of Dayton is a fellowship of over 200 diverse business and professional leaders who commit their time and talent to staying informed and serving the club, the community and the world.

The Rotary club of Dayton was organized May 27, 1912 and was chartered as the 47th club of Rotary International on June 2, 1913.

Orville Wright, the inventor of flight, was an early member of the Rotary Club of Dayton. Dayton Rotarians have witnessed both the Wright Flyer’s first flight and moon landings. We have taken the automobile from an open carriage, to efficient battery-operated vehicles. We have witnessed partyline telephones go to hand-held wireless devices carried by everyone. Entertainment went from radio to the television to computers that are small enough to fit in our purse or pocket and carry on planes.

The Rotary Club of Dayton was once a business-only club that mirrored Paul Harris’s thinking of what Rotary should be: Businessmen learning about each other’s business, doing business with each other based on a foundation of trust.

The Rotary Club of Dayton today is a group of current and future leaders who work in government, in the corporate world or in the not-for-profit world while we focus on building productive relationships and serving our community. We are individuals from different genders, different races, different backgrounds, and different religions. And we are resilient! During COVID we continued to meet via zoom and now every Monday over lunch we do a hybrid meeting, in person at Sinclair College as well as over zoom.

Darke Side of the Moon KitchenAid Pop-Up Sale

Greenville Whirlpool Operations will hold a KitchenAid Pop-Up Shop from Friday, April 5 until Monday, April 8, 2024, in conjunction with the community events during the weekend of the Solar Eclipse.

The store’s hours of operation will be 8 AM – 4 PM, and its location is 365 Martin Street, Greenville, Ohio 45331 (between the old Marsh building and Subway, right off of Broadway).

Note: this sale is not a fundraiser like our past Annie Oakley sales; it’s another great way to engage with Darke County residents and visitors who are here to enjoy the events offered by local businesses during the Solar Eclipse weekend.

Lyle Lovett Returns to The Rose

4x GRAMMY Award-winning singer, composer and actor Lyle Lovett will embark on an extensive tour this summer with his Large Band. The tour will include a stop in Huber Heights, OH for a performance at Rose Music Center at The Heights on Friday, July 26.

Whether touring with his Large Band, Acoustic Group, or in conversation and song format, Lovett’s live performances show not only the breadth of the Texas legend’s talents, but also the diversity of his influences, making him one of the most compelling and captivating artists in popular music.

The upcoming performances will feature songs from across Lovett’s extensive catalog, including his latest album, 12th of June, which was produced by Lovett and Chuck Ainlay. Coupled with his gift for storytelling, the record further highlights Lovett’s ability to fuse elements of jazz, country, western swing, folk, gospel and blues in a convention-defying manner that breaks down barriers. Of the album, The Wall Street Journal hails, “Few artists can bring all of these moods and sounds into one place and put a personal stamp on them all; Lyle Lovett does that.”

Lovett has broadened the definition of American music in a career that spans 14 albums. Since his self-titled debut in 1986, he has evolved into one of music’s most vibrant and iconic performers. Among his many accolades, besides four Grammy Awards, he was given the Americana Music Association’s inaugural Trailblazer Award, was named Texas State Musician and is a member of both the Texas Heritage Songwriters’ Association Hall of Fame and the Texas Cowboy Hall of Fame.

Tickets will go on sale to the public beginning at 10AM on Friday, March 22 at Ticketmaster.comand the Rose Music Center Box Office.

Downtown Bourbon Chicken Eatery To Close Thursday

There’s a little restaurant hiding in the basement of the Talbott Tower in downtown Dayton called Homestyle Chili & Bourbon Chicken. This places had two main dishes, Bourbon Chicken and Chili. There are other items on the menu such as Hamburgers, backed tilapia, gyros, cheese steaks and hot dogs, but the chicken and chili are what they are known for, as well as great service and friendly staff.

But after 13 years at this location, Thurs, Feb 29th will be their last day of business at the Ludlow Street location. According to a post on Facebook by Kal El “he will be moving to a new location! Don’t know all the details yet but rest assured they will be back and moving soon.”

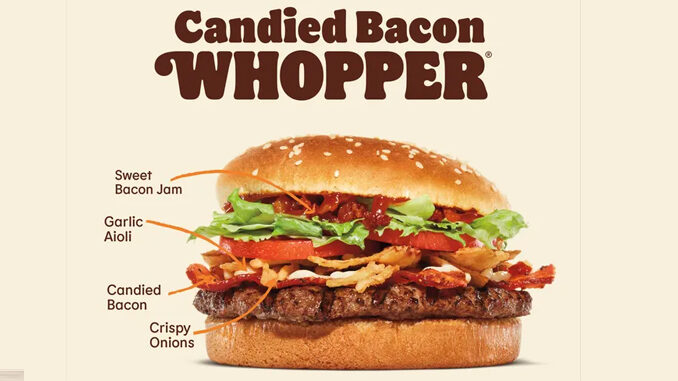

New Candied Bacon Whopper Available at Burger King

The Candied Bacon Whopper will feature the classic 1/2 pound flame-grilled beef patty, topped with crispy fried onions, garlic aioli, sweet bacon jam, and brown sugar candied bacon on a sesame seed bun. Customers can grab the limited edition sandwich while supplies last.

You can find the new Candied Bacon Whopper now at participating BK locations nationwide for a limited time while supplies last.

Unplugged Vibes with Velvet Crush

Start your weekend right with the acoustic tunes of Velvet Crush. No cover charge – just pure musical enjoyment!

This Must Be the Party hits the stage this Friday at The Brightside

One of the most celebrated music events in Dayton during the last decade is back! This Must Be the Party is a local super group who performs a fantastic tribute to The Talking Heads. Fans love the complete recreation of the classic album and documentary film Stop Making Sense that they perform! Catch them for an exclusive show Friday April 14, 2023 at The Brightside, in downtown Dayton.

One of the most celebrated music events in Dayton during the last decade is back! This Must Be the Party is a local super group who performs a fantastic tribute to The Talking Heads. Fans love the complete recreation of the classic album and documentary film Stop Making Sense that they perform! Catch them for an exclusive show Friday April 14, 2023 at The Brightside, in downtown Dayton.

Few bands are as well-known in the music industry as the Talking Heads. The band, which was founded in the middle of the 1970s, contributed to the development of a new musical genre that would later come to rule the radio in the 1980s. The Talking Heads were one of the most innovative and forward-thinking bands of their period with their special fusion of rock, groove, and New Wave. It’s no wonder that Dayton audiences love this tribute show!

Due to the Covid shutdown, This Must Be the Party hasn’t performed since 2019, so this is a highly anticipated event! The best part is that part of the proceeds from this show go to benefit The Seedling Foundation, an organization that supports the arts magnet at Stivers School for the Arts. It’s a musical celebration to support music education!

If you’ve had the pleasure of seeing this amazing show already, you know how much fun to expect! (Pro tip: Wear comfortable shoes!) This go around, there is a very special guest joining the show. Sammi Garett, from the national touring acts Turquaz, Cool Cool Cool, & The Bump Assembly, is flying in from Brooklyn to join the crew! She’s an absolutely fabulous singer and performer, and she’s excited to perform in Dayton for the first time.

If you’ve had the pleasure of seeing this amazing show already, you know how much fun to expect! (Pro tip: Wear comfortable shoes!) This go around, there is a very special guest joining the show. Sammi Garett, from the national touring acts Turquaz, Cool Cool Cool, & The Bump Assembly, is flying in from Brooklyn to join the crew! She’s an absolutely fabulous singer and performer, and she’s excited to perform in Dayton for the first time.

Local original band, Intergalactic Space Force, is kicking off the show at 8:30pm, shortly after doors open. They were Dayton Battle of the Bands finalists last year, and always love an opportunity to perform at The Brightside.

After the Stop Making Sense headlining show, if you’re still ready to boogie, Freekbass will be making his Brightside debut with a “Solo Grooves” after party.

After the Stop Making Sense headlining show, if you’re still ready to boogie, Freekbass will be making his Brightside debut with a “Solo Grooves” after party.

If you get hungry, the venue has coordinated with Phat & Rich to be on site to serve your needs. The Mexican inspired cuisine is a hit with concert goers, so go hungry and hang on the Brightside’s awesome patio between sets.

If you’re looking for a place to pre-game, organizers recommend going to Tender Mercy for their amazing cocktails. “Not only is Tender Mercy our neighbor, they are one of the primary sponsors of this event!” event organizer, Libby Ballengee told us. “Their sister restaurant Sueño, is an amazing spot for dinner too, but I’d get reservations first!”

This Must Be the Party promises to be one of the most memorable events of the spring!

*The band includes: Khrys Blank, Nathan Lewis, Patrick Himes, Brian Hoeflich, Erich Reith, Aaron Holmes, Matt Byanski, Eric Cassidy, Nathan Peters, Christopher Corn, Brian Spirk, with special guest Sammi Garett.

HOW TO GO?

When: April 14, 2023

Where: The Brightside Music & Event Venue, 905 E 3rd St, Dayton, OH

– $30 Advance General admission tickets (highly recommend purchasing advance to guarantee spot)

– $35 Day of show

TICKET LINK: https://www.venuepilot.co/events/69946/orders/new

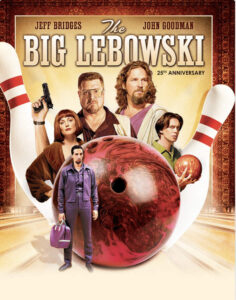

The Big Lebowski Movie Party happening at The Brightside

Dayton Dinner Theater’s Big Lebowski Movie Party is happening at The Brightside this Sunday, March 12, 2023.

Dayton Dinner Theater’s Big Lebowski Movie Party is happening at The Brightside this Sunday, March 12, 2023.

DDT is a great way to spend time with family and friends when the days are short and nights are long. Make the most of it by sipping the sublime themed drinks with your loved ones, while flaunting your movie-themed attire.

What to expect from a Dayton Dinner Theater event? First off, make sure you indulge in the creatively themed food provided by Brock Masterson catering. While you indulge in the delicacies, you can feast your ears to live music and soundtrack presentations featuring acts by the likes of The University of Dayton Jazz Ensemble and acclaimed musician and producer Denny Wilson.

That’s not all. As it’s an interactive movie party, organizers will feature famous interactive quote and fun participation activities, pop-up fun facts, and our not-so-famous, but equally entertaining, theme-spotting drinking game. Enjoy some lip-smacking-themed desserts while you’re at it! To add the cherry on the cake, there are special surprises for the top costume contest participants.

That’s not all. As it’s an interactive movie party, organizers will feature famous interactive quote and fun participation activities, pop-up fun facts, and our not-so-famous, but equally entertaining, theme-spotting drinking game. Enjoy some lip-smacking-themed desserts while you’re at it! To add the cherry on the cake, there are special surprises for the top costume contest participants.

This is the last DDT event of the season. Their movie party series runs from the fall through early spring every year, so you won’t want to miss this opportunity to experience all the fun!

Read more below about the specifics for this movie party!

World Famous Themed Cocktails:

“The Dude Abides” – Captain, Malibu, Melon and Orange Liqueur, and pineapple juice

“The Caucasian” – Vodka, Kahlua, and half and half with a bowling ball drink pick

“The Lady Friend”- Pink lemonade and sprite with fresh lemons

Themed Attire: Pick your character…. Slacker robe and sandals, Nihilist-Euro trash, porn star, Jesus leisure suit, regular bowler guy, urban combat vet, etc …

HOW TO GO?

HOW TO GO?

Mar 12, 6:00 PM

The Brightside, 905 E 3rd St, Dayton, OH 45402, USA

DDNews Discontinues Printing Saturday Paper

Cox First Media will begin printing the Dayton Daily News, Springfield News-Sun and Journal-News six days a week, eliminating the Saturday printed edition on May 6. Though there will be no home delivery or single copy Saturday paper, the Saturday edition will be available through all digital channels, including the daily ePaper, newsletters and websites.

Cox First Media will begin printing the Dayton Daily News, Springfield News-Sun and Journal-News six days a week, eliminating the Saturday printed edition on May 6. Though there will be no home delivery or single copy Saturday paper, the Saturday edition will be available through all digital channels, including the daily ePaper, newsletters and websites.

Every day, more loyal subscribers and more new readers are getting their news online as the evolution toward digital journalism accelerates. Currently, most newspaper readers rely on digital products for trusted local news.

Ending the Saturday print edition will help manage the escalating cost of producing and delivering the printed newspaper. There is no anticipation of further reductions, though the company will continue to align resources to serve the most readers.

Cox First Media is well-prepared for the transition to digital media. In the past two years, print and digital content production has been gathered into one team. Advertising and operations have aligned to support all print and digital products. Cox First Media is connecting a growing online audience to the community, the region and the businesses that serve it.

Every subscription to a Cox First Media newspaper includes daily access to every digital product and website for the Dayton Daily News, Springfield News-Sun and Journal-News.

The parent company of Cox First Media is Cox Enterprises, Inc. which began in Dayton, Ohio with the purchase of the Dayton Daily News 125 years ago. The company was founded on a passion for serving the community with quality news and has always been driven by innovation and change. Throughout its history and continuing today, Cox Enterprises is a leader in the media industry with a commitment to growing and nurturing credible, fact-based journalism.

Retail Lab Accepting Applications Deadline July 13

The Downtown Dayton Partnership (DDP), along with its small business development partners, is inviting business owners to apply to the Retail Lab small business accelerator program, presented by Fifth Third Bank. Launched in 2020, the Retail Lab is an intensive 12-week experience for business owners aiming to launch or grow their first-floor business in downtown Dayton. Applications will be accepted through July 13.

The Downtown Dayton Partnership (DDP), along with its small business development partners, is inviting business owners to apply to the Retail Lab small business accelerator program, presented by Fifth Third Bank. Launched in 2020, the Retail Lab is an intensive 12-week experience for business owners aiming to launch or grow their first-floor business in downtown Dayton. Applications will be accepted through July 13.

The Retail Lab has two main goals: To continue energizing downtown with vibrant storefronts, and provide a supportive pathway into the downtown market for emerging first-floor entrepreneurs, especially women-owned and minority-owned businesses.

“We’re very pleased at the results this program has produced so far in its first four cohorts,” said Sandra K. Gudorf, president of the DDP. “With these new mixed-use spaces emerging, there is an opportunity to take new business ideas and budding entrepreneurs and show them the support network available in our community to grow or launch their own commercial ventures.”

Kia Wilson of Me’ Yanna Berry Co.

The Retail Lab will provide a series of workshops, focused one-on-one sessions and a public speaking event that connects the participating businesses to people, ideas, capital and resources to help them thrive and grow in downtown Dayton. Weekly workshops will include facilitated instruction and work sessions with mentors, and the program will culminate with a pitch competition.

Eligible businesses include boutiques, shops, cafes, galleries and restaurants – any consumer business that adds to the vibrancy of downtown’s sidewalks. Applicants should either be located in downtown Dayton or aiming to launch downtown in the next 6 to 12 months. Ideal applicants will have had a year or so of sales online and/or pop-up events. Interested small business owners can find more information, including the program application, at DowntownDayton.org/retail-lab. Applications for the Downtown Dayton Retail Lab will be accepted through July 13, with classes slated to begin in August. Workshops will be held in person at the DDP office at 10 W. Second St.

Owners Keon McCarroll and Shanti Sancho at the April ribbon cutting for Sole Touchers

“Since the launch of the program in 2020, the Retail Lab has graduated 37 people through the program,” said Val Beerbower, director of first-floor development and business marketing with the DDP and coordinator of the Retail Lab program. “We’re especially proud of the fact that 35 of those 37 businesses are woman-owned, and/or minority-owned businesses. We plan to continue efforts to create equitable economic opportunities through programs like the Retail Lab.”

Participation in the 12-week program is provided at no cost, and in addition to the support businesses receive through the workshops, each participant is eligible for up to $2,500 in professional services from creative, legal, and financial firms to advance their business.

Sonic Introduces New Big Dill Cheeseburger And New Pickle Fries

Sonic has introduced the Big Dill Cheeseburger and new Pickle Fries starting May 2, but if you’ve got the Sonic App you can try it starting April 25, 2022. These new menu items are slated to stick around through June 26, 2022,

The new Big Dill Cheeseburger features a 100 percent pure seasoned beef patty stacked with crispy pickle fries, crinkle-cut pickle slices, a creamy dill-infused ranch sauce, chopped lettuce, and melty American cheese, all layered on a toasted brioche bun.

New Pickle Fries are a twist on traditional fried pickles, featuring dill pickle spears cut in a fry shape, coated in a light tempura coating and fried up until crispy. They come served with a side of ranch sauce for dipping.

App users can also try The Big Dill Cheeseburger for half price when ordering online or in the Sonic App starting May 2, 2022.

STYX and REO SPEEDWAGON Co-Headline US Summer Tour with Loverboy

It’s been four years since legendary rockers REO Speedwagon and Styx joined forces for a summer co-headlining tour. While the world has changed since then, fans’ desire to rock out hasn’t. Styx and REO Speedwagon are telling you to close those laptops and get out of your sweatpants, because they’re set to once again bring their rock & roll classics to the masses, this time with special guestLoverboy for the “Live & UnZoomed” tour that kicks off May 31, 2022 in Grand Rapids and will include a stopin Cincinnati, OH at Riverbend Music Center on Saturday, June 11th.

Check out this video to learn more about the REO Speedwagon/Styx/Loverboy “Live & UnZoomed” tour.

Tickets for the Cincinnati show go on sale to the public beginning at 10AM on Friday, December 10 atTicketmaster.com and Riverbend.org. Styx and

REO Speedwagon will be offering VIP packages via their own exclusive pre-sales beginning Monday, December 6 at 10am local time at REOSpeedwagon.com and StyxWorld.com.

Citi is the official presale credit card of the U.S. “Live & UnZoomed” tour dates. As such, Citi cardmembers will have access to purchase presale tickets beginning Tuesday, December 7 at 10am local time until Thursday, December 9 at 10pm local time through Citi Entertainment. For complete presale details, visitwww.citientertainment.com.

Styx’s Tommy Shaw agrees, “I can’t think of a better way of touring the USA next year than with good friends we’ve known for years and performed with on many a stage. What a great night of music this will be!”

REO Speedwagon’s Kevin Cronin said, “Tommy (Shaw) and I have done a number of Zoom performances together during the pandemic, and REO and Styx are ready to go get UnZoomed, and out on the road for our fifth U.S. tour together. Add our great friends Mike Reno and the Loverboy guys, and I am totally psyched. If I wasn’t performing in it, I would totally come out to see this show. See you all, LIVE and UNZOOMED!”

REO Speedwagon’s Kevin Cronin said, “Tommy (Shaw) and I have done a number of Zoom performances together during the pandemic, and REO and Styx are ready to go get UnZoomed, and out on the road for our fifth U.S. tour together. Add our great friends Mike Reno and the Loverboy guys, and I am totally psyched. If I wasn’t performing in it, I would totally come out to see this show. See you all, LIVE and UNZOOMED!”

Loverboy’s Mike Reno proclaimed, “We can’t wait to take the stage and rock this summer, it’s gonna be awesome. These are all the groups I grew up with, and I’m there too. Best tour of the summer…guaranteed.”

A new era of hope, survival, and prosperity comes calling with the release of CRASH OF THE CROWN, Styx’s new “masterpiece” studio album, which was written pre-pandemic and recorded during the trying times of the pandemic. The multi-Platinum rockers–James “JY” Young (lead vocals, guitars), Tommy Shaw (lead vocals, guitars), Chuck Panozzo (bass, vocals), Todd Sucherman (drums, percussion), Lawrence Gowan (lead vocals, keyboards) and Ricky Phillips (bass, guitar, vocals)–released their 17th album June 18, 2021 on the band’s label, Alpha Dog 2T/UMe, which is available as clear vinyl, black vinyl, CD on digital platforms. They released more new music on September 17, 2021, THE SAME STARDUST EP, originally sold as part of Record Store Day (June 12, 2021). Available on blue 180-gram 12-inch vinyl only, featuring two brand-new songs on side one (“The Same Stardust” and “Age of Entropia”), as well as five live performances on side two of some of Styx’s classic hits previously heard during their “Styx Fix” livestreams that have been keeping fans company during the pandemic on their official YouTube page, including “Mr. Roboto,” “Man In The Wilderness,” “Miss America,” “Radio Silence,” and “Renegade.” It’s available worldwide on all digital platforms.

A new era of hope, survival, and prosperity comes calling with the release of CRASH OF THE CROWN, Styx’s new “masterpiece” studio album, which was written pre-pandemic and recorded during the trying times of the pandemic. The multi-Platinum rockers–James “JY” Young (lead vocals, guitars), Tommy Shaw (lead vocals, guitars), Chuck Panozzo (bass, vocals), Todd Sucherman (drums, percussion), Lawrence Gowan (lead vocals, keyboards) and Ricky Phillips (bass, guitar, vocals)–released their 17th album June 18, 2021 on the band’s label, Alpha Dog 2T/UMe, which is available as clear vinyl, black vinyl, CD on digital platforms. They released more new music on September 17, 2021, THE SAME STARDUST EP, originally sold as part of Record Store Day (June 12, 2021). Available on blue 180-gram 12-inch vinyl only, featuring two brand-new songs on side one (“The Same Stardust” and “Age of Entropia”), as well as five live performances on side two of some of Styx’s classic hits previously heard during their “Styx Fix” livestreams that have been keeping fans company during the pandemic on their official YouTube page, including “Mr. Roboto,” “Man In The Wilderness,” “Miss America,” “Radio Silence,” and “Renegade.” It’s available worldwide on all digital platforms.

Formed in 1967, signed in 1971, and fronted by iconic vocalist Kevin Cronin since 1972, REO Speedwagon’s unrelenting drive, as well as non-stop touring and recording jump-started the burgeoning rock movement in the Midwest. Platinum albums and radio staples soon followed, setting the stage for the release of the band’s explosive HI INFIDELITY in 1980, which contained the massive hit singles “Keep On Loving You” and “Take It On the Run.” That landmark album spent 15 weeks in the No. 1 slot and has since earned the RIAA’s coveted 10X Diamond Award for surpassing sales of 10 million units in the United States.

From 1977 to 1989, REO Speedwagon released nine consecutive albums all certified Platinum or higher. Today, REO Speedwagon has sold more than 40 million albums around the globe, and Cronin and bandmates Bruce Hall (bass), Neal Doughty (keyboards), Dave Amato (guitar), and Bryan Hitt (drums) are still electrifying audiences worldwide in concert with hits and fan-favorites such as “Ridin’ The Storm Out,” “Can’t Fight This Feeling,” “Time For Me To Fly,” “Roll With The Changes,” “Keep On Loving You,” “Take It On the Run,” and many, many more.

REO Speedwagon remained busy throughout the pandemic before the band was able to return to the road. Beginning in April 2020, Cronin began a series of webisodes from his home titled “Songs & Stories From Camp Cronin.” Consisting of anecdotes and acoustic performances from him and his family, the series posted 24 episodes. Cronin and members of REO gave back over the past 16 months by participating in charity events for St. Jude Children’s Hospital, Marilou & Mark Hamill’s USC McMorrow Neighborhood Academic Initiative, John Oates’ “Oates Song Fest,” “Stars to the Rescue,” Acoustic-4-A-Cure, and more. Additionally, while Cronin began keeping a journal of the band’s 2016 UK tour, he never stopped writing and recently submitted what turned out to be his life story, as well as his telling of REO Speedwagon’s history. He says, “Putting out an autobiography is risky. Once it’s out there’s nowhere to hide!” More information on his autobiography will be released shortly.

For more than 40 years, Loverboy has been “Working for the Weekend” (and on the weekend), delighting audiences around the world since forming in 1979, when vocalist Mike Reno was introduced to guitar hot shot Paul Dean – both veterans of several bands on the Canadian scene – at Calgary’s Refinery Night Club. Along with Reno and Dean, Loverboy still includes original members Doug Johnson on keyboards and Matt Frenette on drums, with Ken “Spider” Sinnaeve replacing the late Scott Smith on bass.

For more than 40 years, Loverboy has been “Working for the Weekend” (and on the weekend), delighting audiences around the world since forming in 1979, when vocalist Mike Reno was introduced to guitar hot shot Paul Dean – both veterans of several bands on the Canadian scene – at Calgary’s Refinery Night Club. Along with Reno and Dean, Loverboy still includes original members Doug Johnson on keyboards and Matt Frenette on drums, with Ken “Spider” Sinnaeve replacing the late Scott Smith on bass.

With their trademark red leather pants, bandannas, big rock sound and high-energy live shows, Loverboy has sold more than 10 million albums, earning four multi-platinum plaques, including the four-million-selling GET LUCKY, and a trio of double-Platinum releases in their self-titled 1980 debut, 1983’s KEEP IT UP and 1985’s LOVIN’ EVERY MINUTE OF IT. Their string of hits includes, in addition to the anthem “Working for the Weekend,” such arena rock staples as “Lovin’ Every Minute of It,” “This Could Be the Night,” “Hot Girls in Love,” “The Kid is Hot Tonite,” “Notorious”, “Turn Me Loose,” “When It’s Over,” “Heaven In Your Eyes” and “Queen of the Broken Hearts.” In March 2009, the group was inducted into the Canadian Music Hall of Fame at the Juno Awards show in Vancouver.